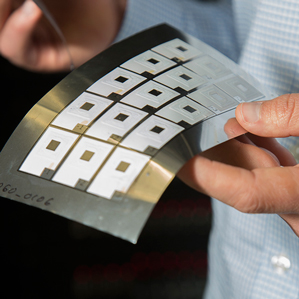

According to MIT Technology Review, a California business is developing flexible, rechargeable batteries that can be printed cheaply on commonly used industrial screen printers. Imprint Energy, of Alameda, Calif., has been testing its ultra-thin, zinc-polymer batteries in wrist-worn devices and hopes to sell them to manufacturers of wearable electronics, medical devices, smart labels and environmental sensors.

The company’s goal is to make batteries safe for on-body applications, while their small size and flexibility will allow for product designs that would have been impossible with bulkier lithium-based batteries.

The company recently secured $6 million in funding to further develop its proprietary chemistry and finance the batteries’ commercial launch. The batteries are based on research that company cofounder Christine Ho began as a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, where she collaborated with a researcher in Japan to produce microscopic zinc batteries using a 3-D printer.

The batteries that power most laptops and smartphones contain lithium, which is highly reactive and has to be protected in ways that add size and bulk. While zinc is more stable, the water-based electrolytes in conventional zinc batteries cause zinc to form dendrites-branch-like structures that can grow from one electrode to the other-shorting the battery. Ho developed a solid polymer electrolyte that avoids this problem, provides greater stability and greater capacity for recharging.

Brooks Kincaid, the company’s cofounder and president, says the batteries combine the best features of thin-film lithium batteries and printed batteries. Such thin-film batteries tend to be rechargeable, but they contain the reactive element, have limited capacity, and are expensive to manufacture. Printed batteries are nonrechargeable, but they are cheap to make, typically use zinc and offer higher capacity.

Working with zinc has afforded the company manufacturing advantages. Because of zinc’s environmental stability, the company did not need the protective equipment required to make oxygen-sensitive lithium batteries.

Despite demand for flexible batteries, Ho says no standard has been developed for measuring their flexibility, frustrating customers who want to compare chemistries. So, the company built its own test rig and began bench-marking its batteries against commercial batteries that claimed to be flexible. Existing batteries failed after fewer than 1,000 bending cycles, she says, while Imprint’s batteries remained stable.

Imprint has been in talks about the use of its batteries in wearables and began working on a project funded by the U.S. military to make batteries for sensors that would monitor the health status of soldiers. Other potential applications include powering smart labels with sensors for tracking food and packages.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG