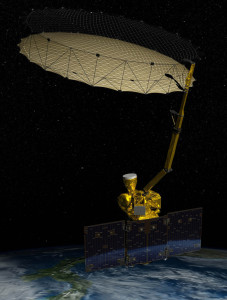

If space is the final frontier, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) just sent a mechanical cowboy into orbit around the earth to round up data about the planet’s soil moisture. NASA’s Soil Moisture Active Passive (SMAP) satellite has three main parts: radar, a radiometer and the largest rotating mesh antenna ever deployed in space. The radar transmits microwaves via the antenna that penetrate the soil, and the radiometer detects differences in returning waves that tell NASA about moisture content in soil. To capture data from the entire planet, the mesh antenna rotates around an extended arm, hence its nickname, “the spinning lasso.”

Northrop Grumman Astro Aerospace in Carpinteria, Calif., has worked on space missions since 1958, devising innovative technology for deployment in harsh conditions. Astro Aerospace’s SMAP antenna is made of a proprietary fabric, AstroMesh®, composed of fine molybdenum wire coated with gold. The wire, made into tricot knit mesh on a large-width knitting machine, has electrical, thermal and radio-frequency-reflective properties that fit the mission of reflecting microwaves to the earth’s surface. Apertures in the mesh range from approximately 10 to 164 feet in diameter, covering radio frequencies from ultra-high frequency (UHF) to beyond Ka-band, 26.5–40 GHz.

The AstroMesh antenna, stowed like a closed umbrella, deploys after orbit on a huge boom that is unfolded robotically. The mesh is stretched across a carbon perimeter truss structure until it looks like a giant tambourine. The boom rotates to project radio frequencies down to the earth’s surface, while the continuous orbit allows for mapping all along SMAP’s trajectory. Read more or see NASA’s description.

“The antenna caused us a lot of angst, no doubt about it,” says Wendy Edelstein, NASA Jet Propulsion Lab. Astro Aerospace designed the antenna and material to fit “a space not much bigger than a tall kitchen trash can” that unfolded into a surface shape accurate to within about an eighth of an inch.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG