The progress of smart fabrics discussed at IFAI’s Advanced Textiles Conference.

Smart fabrics, generally defined as textiles that sense and react to various individual stimuli to provide desired effects or benefits, are now entering their third decade.

Early smart fabrics relied on specially engineered fibers or finishes, while the digital revolution and the Internet of Things (IoT) brought us “wearable” gadgets. The next generation of smart fabrics integrates textiles and technology in electronic or “e-textiles” by incorporating circuitry within a textile structure.

The Advanced Textiles Conference at IFAI Expo 2017 in September offered attendees the opportunity to understand the promise and challenges of this new field through a focused Smart Fabrics Program and E-Textiles Workshop. The series of lectures, roundtable discussions, and hands-on activities explored the markets, applications, functionalities, standards and legal implications of this exciting and relatively new textiles field.

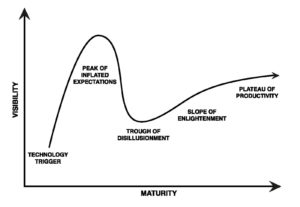

The development of smart fabrics seems much like the journey of the protagonist in Bunyan’s 17th century allegory Pilgrim’s Progress, who faced obstacles on the road to Paradise. More than one presenter at the conference placed the smart textiles industry in the “Trough of Disillusionment” on the Gartner Hype Cycle, a graphed representation of technology development and adoption developed by the Gartner Research technology and advisory firm.

Where is the market?

According to Laurie Mease, trade specialist for the U.S. Dept. of Commerce/Office of Textiles and Apparel (OTEXA), the global market for smart textiles grew by 18 percent from 2012–2016 to $2.75 billion. The U.S. market alone was worth $1.67 billion in 2016, growing 27 percent for the period.

Much of the market is being driven by military and government mandates. Jeff Rasmussen, IFAI’s director of market research, breaks down the 2016 global market for smart textiles into the following segments: transportation, 27 percent; military/government, 21 percent; industrial/commercial workwear, 20 percent; sports/fitness, 17 percent; medical/healthcare, 8 percent; and fashion/entertainment, 7 percent.

As a subset of smart fabrics, e-textiles are finding commercial success particularly challenging. Beyond textiles that monitor heartbeats, respiration, and motion; protective devices; and communication devices such the Google/Levi’s jacket, some e-textiles technologies remain in the early stages of development.

“Electronics and textiles have competing goals,” said Jesse Jur, associate professor, Dept. of Textile Engineering, Chemistry and Science (TECS) at the College of Textiles, North Carolina State University (NCSU). “For electronics, it’s function first. For textiles, it’s comfort first. Success depends on integration with existing ecosystems.”

Rasmussen believes that e-textiles’ development is challenged by economics of production, a lack of critical mass and the need for industry standards, particularly with regard to laundering and performance.

The Advanced Functional Fabrics of America (AFFOA) center for prototyping advanced fabrics, which opened its national headquarters at MIT in June, will help facilitate the growth of smart textiles, Rasmussen predicts. The AFFOA was created in 2016 with $300 million in funding from a consortium of U.S. and state governments, as well as academic and corporate partners.

Identifying the need

“Smart textiles need to be more than ‘cool technology,’” Mease points out. “They need to fulfill an unmet need, and provide a solution.”

“No one in this industry is making any money because there is not yet a market need,” Dr. Jur says. He sees health care and energy harvesting as areas for potential growth.

The Textile Engineering/Textile Technology Senior Design course at NCSU, co-directed by Jur and Russell Gorga, professor and associate head director of the school’s TECS undergraduate program, couples students with companies in year-long product development projects that begin with identifying the user needs. “Innovation is dependent on the ability to creatively solve an open-ended problem,” the two believe.

“We’re looking to bridge the gap between technology and the apparel, textile and footwear business,” says Ben Cooper, managing director of IOClothes, a consultancy specializing in the development of products incorporating smart fabrics and e-textiles. He predicts the scale-up of smart textile supply chains, standards, new business models and more compelling uses beyond sports and fitness within the next three to five years.

Form factors, systems and standards

Behind any smart textile lies a matrix of materials that must be designed to work as a system. Key to e-textiles is the integration of the textile substrate and the electronic circuitry. Conductive yarns can be knit, woven, sewn or embroidered into textile substrates to lay the groundwork for e-textiles.

Marubeni’s Electro-Yarn is a polyester multifilament coated with carbon nanotubes. Introduced by Supreme Corp., the VOLT Apache range of smart yarns includes blends of wool/nickel and polyester filament coated with copper or stainless steel for high levels of conductivity.

Printed circuitry using electronic inks and pastes is the latest innovation in creating conductive pathways. DuPont’s Intexar™ inks are screen printable in simple or complex patterns on a TPU film, which is then laminated to a fabric. The resulting e-textile is flat, light, and stretchy.

Traditional textile mills are beginning to work with such products—some tentatively, others with more enthusiasm—in partnership with their customers. “We have more customers looking for textile matrices to support their e-textile development,” says Bill Christmann, vice president of sales and marketing for Gehring-Tricot.

However, without industry-wide standards for performance as well as for aftercare, it’s a bit of trial-and-error. There’s much discussion suggesting that the establishment of standards would help promote innovation and reduce delays.

Standards organizations such as the American Association of Textile chemists and Colorists (AATCC), ASTM International, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) and the IPC are working with smart textiles innovators and other stakeholders to develop appropriate standards.

Gerry Elman, president of Elman Technology Law, says, “We need effective and appropriate safety standards for issues such as physical safety and privacy.”

The path forward

Perhaps the biggest challenge for smart fabrics is that there is more than one right answer to any problem. Eva Osborne, vice president of research and innovation for smart textile incubator Significant Difference, and an E-Textiles Workshop host at IFAI EXPO, has an open-ended point of view about the future of smart fabrics. “Does it make sense? Who cares? We don’t have enough experience to know where we’re going. But the millennials want it—and they don’t think like baby boomers!”

Connie Huffa, whose engineering lab Fabdesigns develops cutting-edge knit performance and smart fabrics for footwear, military, medical and aerospace end uses, sees intrinsic value in these new-age fabrics. “Smart textiles will help us connect, and will have multiple functions and longevity. They will transition with our environments and not be thrown away.”

Debra Cobb is a freelance writer based in Greensboro, N.C., with extensive experience in the textiles industry. She is a regular contributor to Advanced Textiles Source.

TEXTILES.ORG

TEXTILES.ORG